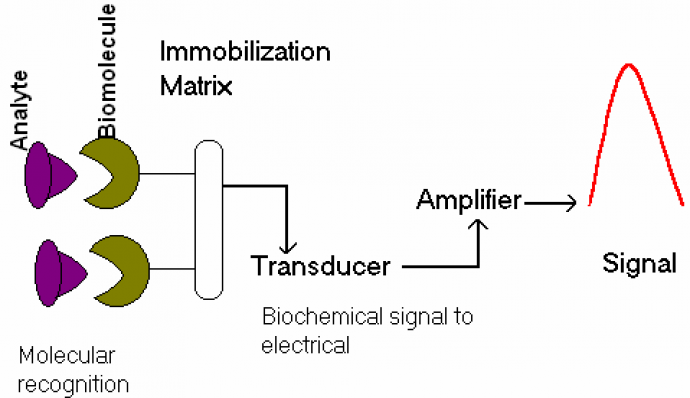

Cross bridge theory

The cross-bridge theory of muscle contraction states how force is produced, and how the filaments actin and myosin are moved relative to each other to produce muscle shortening. In the cross-bridge theory, sidepieces that are fixed in a regular pattern on the myosin filament (cross-bridges) are thought to undergo cyclic attachment and detachment to specific binding sites on the actin filament. During an attachment/detachment cycle, the cross-bridge head is thought to undergo a rotation and so pull the actin filament relative to the myosin. Each of these cycles is associated with a relative movement of ∼10 nm and a force of about 2–10 pN. Furthermore, one cross-bridge cycle is thought to occur with the energy gained from the hydrolysis of one adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

The cross bridge theory explains the mechanism of muscle contraction based on muscle proteins that slide past each other to generate movement. According to this theory, the myosin (thick) filaments of muscle fibers slide past the actin (thin) filaments during muscle contraction, while the two groups of filaments remain at relatively constant length.

It was independently introduced in 1954 by two research teams, one consisting of Andrew F. Huxley and Rolf Niedergerke from the University of Cambridge, and the other consisting of Hugh Huxley and Jean Hanson from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was originally conceived by Hugh Huxley in 1953. Andrew Huxley and Niedergerke introduced it as a “very attractive” hypothesis.

Force-Length Relationship

Due to the presence of titin, muscles are innately elastic. Skeletal muscles are attached to bones via tendons that maintain the muscle under a constant level of stretch called the resting length. If this attachment was removed, for example if the bicep was detached from the scapula or radius, the muscle would shorten in length.

This line graph depicts the relationship between tension and length in the sarcomere.The Ideal Length of a Sarcomere: Sarcomeres produce maximal tension when thick and thin filaments overlap between about 80 percent to 120 percent, approximately 1.6 to 2.6 micrometers.

Muscles exist in this state to optimize the force produced during contraction, which is modulated by the interlaced myofilaments of the sarcomere. When a sarcomere contracts, myosin heads attach to actin to form cross-bridges. Then, the thin filaments slide over the thick filaments as the heads pull the actin. This results in sarcomere shortening, creating the tension of the muscle contraction. If a sarcomere is stretched too far, there will be insufficient overlap of the myofilaments and the less force will be produced. If the muscle is over-contracted, the potential for further contraction is reduced, which in turn reduces the amount of force produced.

Simply put, the tension generated in skeletal muscle is a function of the magnitude of overlap between actin and myosin myofilaments.

In mammals, there is a strong overlap between the optimum and actual resting length of sarcomeres.

Force-Velocity relationship

Force-Velocity Relationship: As velocity increases force and therefore power produced is reduced. Although force increases due to stretching with no velocity, zero power is produced. Maximum power is generated at one-third of maximum shortening velocity.

The force-velocity relationship in muscle relates the speed at which a muscle changes length with the force of this contraction and the resultant power output (force x velocity = power). The force generated by a muscle depends on the number of actin and myosin cross-bridges formed; a larger number of cross-bridges results in a larger amount of force. However, cross-bridge formation is not immediate, so if myofilaments slide over each other at a faster rate the ability to form cross bridges and resultant force are both reduced.

At maximum velocity no cross-bridges can form, so no force is generated, resulting in the production of zero power (right edge of graph). The reverse is true for stretching of muscle. Although the force of the muscle is increased, there is no velocity of contraction and zero power is generated (left edge of graph). Maximum power is generated at approximately one-third of maximum shortening velocity.

Muscle contraction velocity

Skeletal muscle contractions can be broadly separated into twitch and tetanic contractions. In a twitch contraction, a short burst of stimulation causes the muscle to contract, but the duration is so brief that the muscle begins relaxing before reaching peak force. If another contraction occurs before complete relaxation of a muscle twitch, then the next twitch will simply sum onto the previous twitch, a phenomenon called summation. If the stimulation is long enough, the muscle reaches peak force and plateaus at this level, resulting in a tetanic contraction.

References: